Human perception of light and color has many curious features rooted in biology and physics. However, there is a more immediate practical discipline, called Color Theory, that deals with the engineering questions of the base pigments (or colored lights) that we need to vividly reproduce any other color. We will briefly explore this discipline here.

Colors

Whether you’re walking through a lush forest or an art museum, our world is full of colors. Colors enhance a painting’s beauty and make our homes and schools much more fun. Colors also have practical uses such as the colors on a stoplight or color-coding your class notes. Let’s explore how colors are made, mixed, and how they emerge from white light!

Perceiving Color

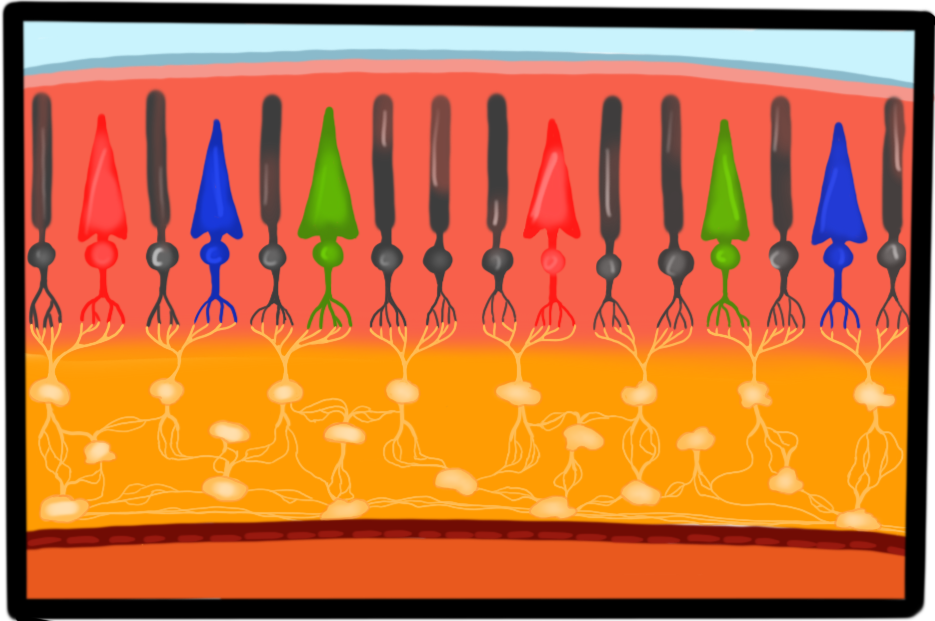

Before we explore how to mix colors, it is useful to understand some basics of how the human eye works. At the back of our eye, there is a light-sensing tissue called the retina. The retina has some cells that respond to lightcalled rods, which help us see when there is little light, such as at dusk and other cells that respond to specific wavelengths of lightcalled cones, that allow us to see color. The cone cells are classified into three separate groups by the color that they sense the best: red, green, or blue. For instance, the blue-sensing cones respond most to blue light, and allow our brain to perceive blue.

You may have noticed a problem at this point. If our eyes only have sensors for three colors, how do we see other colors, like yellow? We’re able to see more colors because our red- and green-sensing cones both respond slightly to yellow light as well. Our brain then interprets both the red and green sensing cones being activated as yellow. Similarly, our red and blue sensors both have some sensitivity for purple light, allowing us to perceive purple as well.

If this has sparked your curiosity to learn more about how your eye works and how our brain turns that information into all the colors we can see, then try out our Biology of Sight Adventure.

When we mix colors, whether using LEDs (or other sources of light) or pigments (that reflect certain colors of light), understanding how our eyes percieve light is necessary. We’ll return to this information in the rest of this lesson as we explore how to create colors with light and pigments.

Mixing Colors With Light Sources

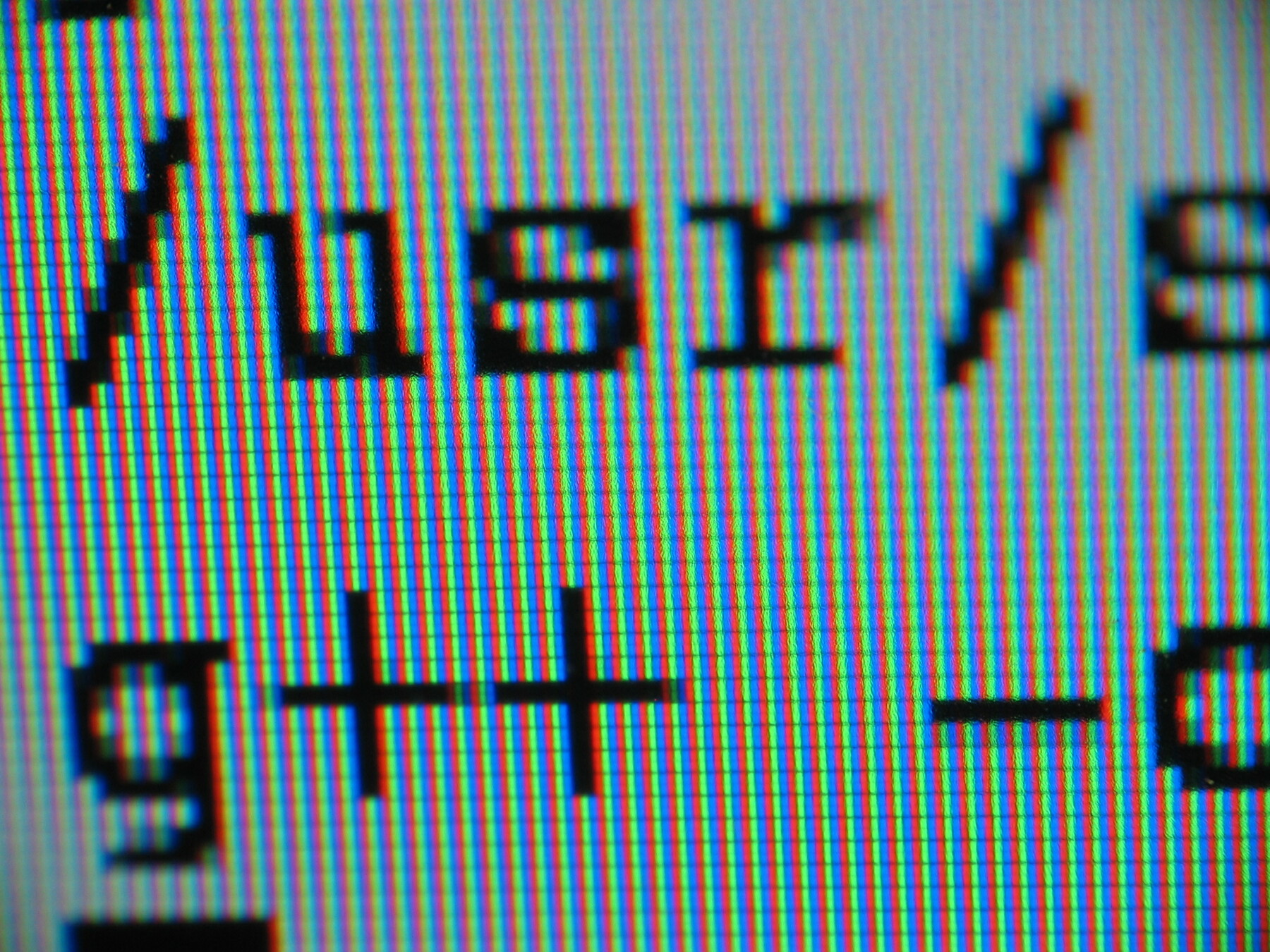

One way to create color is to work directly with light sources that emit colors that match the sensors in our eyes. Computer and TV screens work in this way. These screens are made up of a grid of very small red, green, and blue light sources (pixels and sub-pixels). These colors were chosen because they match the light our cone cells detect. By placing these tiny light sources so close together, our brain sees them as one single light source. Moreover, our eyes can’t distinguish between yellow light which activates both the red and green cones and a mixture of red and green light from light sources sufficiently close together. This way we can trick our brain into seeing not only red, blue, and green, but a whole rainbow of colors.

By varying the amount of the red, green, and blue light emitted, we can trick our brains into perceiving a diversity of color. This type of color mixing is called additive color mixing: each of the colored light sources adds up to a new color. The colormixer below allows you to try mixing color in this way. Looking at the colormixer, notice how with all three slide bars at 255, the box at the right is white. By adjusting the relative amount of green, red, and blue using the slide bars, you can change the color displayed.

Imagine a white ball (i.e. a ball that reflects all of the colors of light falling on it) in a dark room. We shine three lights on it, with different intensity: a red, a green, and a blue light. If we shine them all together, the ball reflects them all and see a white color. Take a moment to play around with these and see if you can make your favorite color! You can see this illuminated ball below the sliders.

Mixing Colors with Pigments

Now let’s explore a type of color mixing that you might be more familiar with: mixing with pigments. If you’ve ever painted before, you’ve probably mixed colors on a palette. When we are painting, we are using the pigments in our paint to reflect light of only certain colors. Color mixing with pigments is frequently called subtractive color mixing because each of our base pigments absorbs a color from the initial ray of white light. The idea of using pigments to create color is used in our clothes, painting our houses, and even coloring our food.

Pigments work by absorbing certain components of light and reflecting others. To read more about colors as components of light, check out our Light and Color lesson.

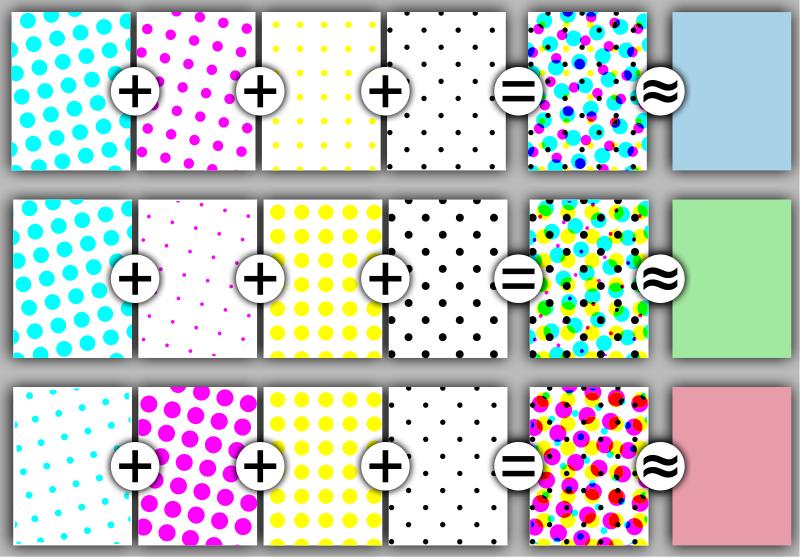

When painting in elementary school, you likely were given red, yellow, and blue to create the rest of the colors you wanted. With these colors you can mix more colors such as green, orange, and purple. You may have struggled to get a true purple or the exact green that you imagined, if you were using only the red, blue, and yellow paints your art teacher provided. The reason for this is that the red and blue pigments that you were given are not the best matches for our eye’s color sensors. Better base pigments for creating vibrant colors are those that a typical printer uses: yellow, cyan (a fancy word for the specific blue that is a primary color), and magenta (the specific almost-red color that is a primary color).

Primary colors are special because they allow you to create all other colors. Primary colors can’t be mixed from other colors, while secondary colors can be created by mixing others. Cyan, yellow, and magenta are primary colors because each of these pigments absorbs the light that best activates one of the three sensors in our eyes. For instance, cyan colored pigments absorb red light and reflect green and blue light.

| Primary Pigment Color (a.k.a. subtractive) |

Complemented by Primary Light Color (a.k.a. additive) |

|---|---|

| Cyan (absorbs red and reflects green and blue) |

Red |

| Magenta (absorbs green and reflects red and blue) |

Green |

| Yellow (absorbs blue and reflects red and green) |

Blue |

At this point, you may be wondering why your art teachers told you that red, yellow, and blue are the primary colors. The reason for this is because historically red, yellow, and blue were thought to be true primaries. However, once we learned more about how the eye works we realized that magenta, yellow, and cyan were much better matches for our eyes’ sensors. The less accurate red, yellow, and blue system persists in elementary art classrooms because many art teachers think it is too difficult to teach young kids the difference between cyan and “primary blue” (also, it is harder to buy bulk paints in cyan and magenta). This makes it harder to mix vibrant colors in art class and to confusion when learning otherwise later on.

If you have ever mixed colors using yellow, cyan, and magenta, you may have noticed how many more colors you can mix using them instead of what we wrongly think of as “primary red, yellow, and blue”. You can experiment with such mixtures by adjusting the sliders below.

Imagine a white sheet of paper (reflecting all colors of white light) on which we add pigments that absorb some colors. That would be cyan (absorbing red and reflecting green and blue), magenta (absorbing green), and yellow (absorbing blue). Adding up these pigments leads to absorbing all colors and reflecting none, making the page black. You can see what the sheet of paper would look like below the sliders.

Experimenting with this colormixer, you may have been able to make green from mixing together cyan and yellow or orange from yellow and magenta. You may have noticed that you could also make the color red that is often introduced in elementary school as a primary color by mixing together magenta and yellow. This is because magenta absorbs blue light, while yellow absorbs green light, thus leaving only red to be reflected.

Did you notice how if you wanted to get a darker green, you could add magenta? Adding magenta makes a darker green because red is green’s complementary color. Adding a color’s “complement” is actually a more effective way to make a darker color than adding black. Complementary colors are opposite each other on the color wheel. This website talks more about complementary colors.

When we were talking about creating color with light sources, we mentioned how our computer screen works by putting tiny light sources of green, red, and blue light so close together that our eyes can’t distinguish between the separate light sources. Color printing works in a similar way, but using tiny dots of yellow, cyan, and magenta ink. By overlaying microscopic dots of color of varying size, color printers can give the illusion of smooth color.

Have you ever noticed how some of your clothes may look a different color when in your room at night versus outside on a sunny day? The light that comes from a light bulb is actually made up of a different combination of colors than sunlight. For that reason, the pigments in your clothes may reflect a different combination of colors back at your eyes under different light sources, changing your perception of the color. This property also explains why a green leaf will look black under red light. The pigmentsmostly a particular molecule called chlorophyll absorb red light and reflect the other colors. Therefore, if only illuminated by red light, all of the light is absorbed, and it appears black.